Susan M. Schultz, from Poem Series with Photography

Meditations

Meditation 63

22 May 2020

Claude lies on two small black slippers this morning. Pushes paws into the slots where feet fit. Lies on one slipper, then flips on his back, grasps slipper to belly. Rubs his gray face on the slipper’s bottom, then covers it, grabs the other slipper, performs a somersault, looks back toward the door where other cats sometimes skulk, returns to the slipper. Were the slippers not plastic, his embrace would kill them. Khmer Rouge cadres wore slippers made of old tires when they killed her father. Memory is a zoom background that slips in and out of a body. She filled her room with cells, kept losing her head to them. Bodies with cells on top. It’s hard to do two things at once on the screen, though one poet read with only one eyebrow and half a furrow showing. Another poet’s selfie featured migrant gray eyebrow hairs. The practice of aging requires discipline, an old woman schlepping across a desert. She focuses on anything that is not sand, demented landscape of cactus and rock outcropping. That’s what shows as new, as most impermanent, what we identify as most like ourselves. “Change mind” was her first favorite phrase in English. Change mind is what her grandmother did, without meaning. We are, without meaning to be. Watch yourself as you want to be in the world. Then subtract reality from desire and want that, too.

Meditation 64

26 May 2020

I can't get away from the man in the park, the man who sat planted like a mirrored C on a picnic bench, back bent, chin to chest. I returned; he was gone, white truck gone, blue lights gone. CLOSED reads the sign on the swing set, held up with yellow tape. My daughter kicks her soccer ball against a wall; an older man, dribbling, fakes out no one, stutter-stepping to the hoop. Lilith reads scents on the concrete walk. In isolation, we make causes to mimic effects. Or we get stuck on causes, losing effects. I can't get away from the man in the park. His isolation fails to mime a two person game. He’s effect without cause, cause without name. His hurt is like the post-it note my cat attacks, before he turns to bite his tail. “That’s a heavy story,” a friend writes. Stories end when we arrive at their predicates, but the ordinary stops short, like a woman leaning over a cliff to count shades of blue in the English channel. Her neighbor, who wears yellow pants, is an “alien” from the sky where dolphins swim. I resist her narrative, but admire the ending, love as sure as sonnets. “I’m ok,” he said. Words, aspiration, a flag to wave me off.

—for Jono Schneider

Meditation 65

1 June 2020

The dead man’s brother breathes grief in, sucking air and expelling it through his mask. On the right, “I can’t breathe”; on the left, “Justice." Everyone takes photos, even masked photographers as they take their knees, or chests. We take a knee, we bend it, we offer it. The officer’s knee was a perversion, his blank face a mask with nothing on it. The dead man’s brother kneels beside the curb where his brother died. He wears a Yankees cap, lives in Brooklyn. A minister lays reassuring hands on his back, his neck. Grief as the inversion of a particular violence. They are a peaceful family, he says. He loved this place; don't burn it down. The president hides in a bunker beneath the White House. There was a bicycle in the bonfire across the street. A white girl rushed out to kneel with a young black man. As the police advanced she put her body between him, their shields and batons. This is time sensitive, but not in exact chronology. Trauma’s time makes an altered sense, like collage, except it keeps falling apart. Too humid for such glue. Elements don’t cohere into proper equations, or chapters in a book. If you don’t let us grieve our dead, we can’t get six feet away. There are no ventilators on the streets to breathe for us. Americans refuse to mourn their bad history; this is the problem entire, a historian argues. I can’t remember her name or her book. A man calls out “say his name!” and those in the circle filled with flowers and peace signs call it out. Breathe in his pain, breathe out love for the broken world he left behind. Watch his brother stand inside the circle, then exit its embrace.

—in memory of George Floyd

Meditation 66

31 May 2020

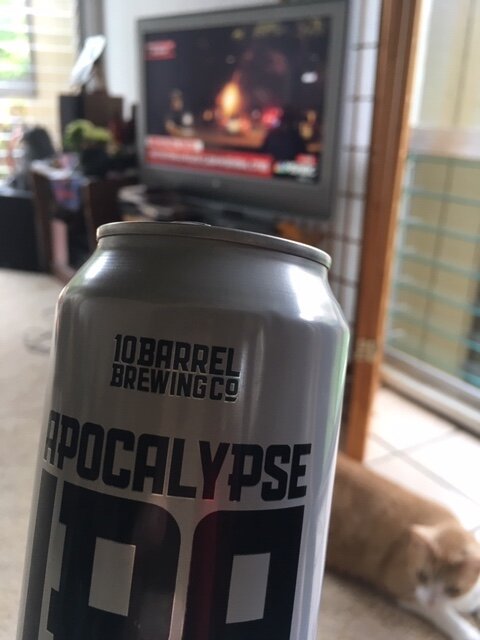

I turn away each time, but it keeps coming back. The white cop, the black man’s head on the ground, police peering in a car, girl weeping who filmed the murder. I turn away, as if to turn my other cheek, but it’s not my cheek to turn. My eyes see in not-seeing. “I loved my brother; why do I have to feel such pain?” There’s acid in the cup that spills over in the street like tear gas, like smoke grenades, like milk that’s use to cut the sting. She asks what the ordinary is now. An orchid pushing open on the lanai; a cop throwing a woman to the ground. Cat curled at my feet; empty clothes scattered on a sidewalk of shattered glass. Shama thrushes in the puakenikeni; “what’s the use of sirens if that’s all you hear?” Neighbors tell me to turn off my television; it doesn’t concern your life, one adds. He’s a good cop. My mother stopped our car on Fort Hunt Road, 50 some years ago, to ask a black man in a stalled car if he needed help. “You know why that policeman just drove by,” she said to me, who did not. At five, I joked back and forth with one of the moving men, until I said in triumph, “you’re a Negro!” What I knew already cannot be forgotten, no matter how often we delete our cell phone clips, turn off the sound, put ourselves under house arrest. You put the rest there, between the sharp and the flat notes. While grieving, Denise Riley notes, time stops for us. It’s as if we’re erased, but still move like we want to be in the world. And we do.

Meditation 67

3 June 2020

Eating the first poisonous tomatoes of America—frightened on the dock. It’s your 94th today, Allen; it was in her 94th year that my mother died, who remembered walking the docks of New York, watching war brides come off Liberty ships, noting their farm-girl incongruities with mothers-in-law dressed to the nines, who wandered the corridors of Arden Courts with such purpose until the falls and the pneumonia installed her in a comfy chair in front of a loud television, who'd begun dying nine years ago and kept on dying until the 14th of June. Someone came to the door and I said, “not now, my mother’s dying.” Her breath came in saccades, and then it stopped. She wasn’t carrying her body but was held by it, and the bones of her thumbs stopped grazing across her narrow hands, every ounce of her energy devoting itself to the end of being. That is my path, a woman said after meditation; the slogan popped into her head. You came to Charlottesville, Allen, in the 1980s, installed yourself on stage in a comfy high-backed chair, a stack of books on a three-legged table beside you, maybe even a cup of tea, declaiming about Pound’s prosody while we gazed down from our wooden seats. Far from Naomi mad on her toilet, or my mother breathing hard on her single bed, far from her home on Lee Jackson Highway near the NRA, the road I never found on the first try. Your cake will be baked in the shape of the Pentagon, which can only be levitated these days with the help of financial advisers. Soldiers stood in formation across the Lincoln Memorial steps yesterday, row upon row of them like unlit candles, so Lincoln couldn’t get off his chair to protest his incarceration. Only the flash of existence, then tear gas rolls down avenues like a mighty stream.

—quoted language from "Kaddish"

Meditation 68

5 June 2020

The point is not to capture an instant, arrest it, put it in cuffs and haul it to jail; nor is it to push it down to the sidewalk, watching it bleed from the head. Memory ought not be incarceration, but opening. The pronoun can’t afford its abstraction; that was an old man pushed to the ground by a policeman. National Guard troops stand shoulder to shoulder in Lafayette Park, behind fences, shining beams of light at protesters on the other side, not to see them, rather not to be seen by them. There were slave auctions in that park. The incarcerated body remains not in the bronze of a statue, but behind the thin skin of a police line. You can fence out skin, but not the breath.

Photos by Susan M. Schultz